Underwater tsunamis created by glacier break-up

Scientists lucky enough to be in the “right place at the right time” witnessed a giant lump of ice breaking away from the William Glacier in Antarctica, a process known as calving.

As the ice - an area about the size of ten football pitches 40 metres above the sea - broke away and tumbled into the ocean, it triggered underwater tsunamis – waves that travel inside the ocean for many kilometres causing the water column to mix.

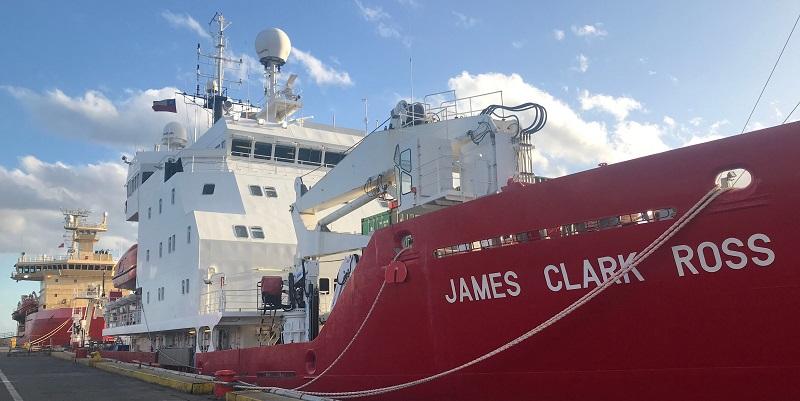

Researchers who were on a nearby research vessel, the British Antarctic Survey’s Royal Research Ship James Clark Ross, were able to measure the way nutrients and heat in the sea were redistributed.

This data will help scientists continue to improve modelling.to better understand ocean dynamics.

But the researchers first needed to determine if the events they had witnessed were a one off or typical of glacier calving.

Video showing ice falling away from the William Glacier. Courtesy: British Antarctic Survey

A team at the University of Leeds used satellite images from the European Space Agency to investigate similar calving events since 2015.

Ben Wallis, a doctoral researcher from the School of Earth and Environment and the Institute for Climate and Atmospheric Science at Leeds, who undertook the image analysis, said: “This work was important because it placed the fieldwork measurements in context, showing that similar events happened in most years and sometimes multiple times per year.

“This demonstrated that the fieldwork observations were not a “one-off” but instead an observation of a process which happens regularly, highlighting its importance for glaciers and oceans in this region and potentially further afield.”

The eyewitness account of the glacier calving and the subsequent investigation of its impact on the seas have been reported in the journal Science Advances.

Ice in Antarctica flows to the coast along glacier-filled valleys. While some ice melts into the ocean, a lot breaks off into icebergs, which range in size from small chunks up to the size of a country.

A team on board the research ship in January 2020 were taking ocean measurements close to the William Glacier, situated on the Antarctic Peninsula, as the front of it dramatically disintegrated into thousands of small pieces.

The British Antarctic Survey’s Royal Research Ship James Clark Ross. Credit: Professor Mike Meredith

Lead author of the study Professor Michael Meredith, who is head of the Polar Oceans team at the British Antarctic Survey, said: “This was remarkable to see, and we were lucky to be in the right place at the right time. Lots of glaciers end in the sea, and their ends regularly split off into icebergs. This can cause big waves at the surface, but we know now it also creates waves inside the ocean.

“When they break, these internal waves cause the sea to mix and this affects life in the sea, how warm it is at different depths and how much ice it can melt.

“This is important for us to understand better. Ocean mixing influences where nutrients are in the water and that matters for ecosystems and biodiversity. We thought we knew what caused this mixing – in summer, we thought it was mainly wind and tides, but it never occurred to us that iceberg calving could cause internal tsunamis that would mix things up so substantially.”

Internal tsunamis have been noticed in a handful of places, caused by landslides. Until now, no one had noticed that they are happening around Antarctica, probably all the time because of the thousands of calving glaciers there. Other places with glaciers are likely affected also, including Greenland and elsewhere in the Arctic.

This chance observation and understanding is important, as glaciers are set to retreat and calve more as global warming continues. This could likely increase the number of internal tsunamis created and the mixing they cause.

Professor Meredith added: “Our fortuitous timing shows how much more we need to learn about these remote environments and how they matter for our planet.”

Further information

For more details, please contact David Lewis in the press office at the University of Leeds: d.lewis@leeds.ac.uk

The paper, Internal tsunamigenesis and ocean mixing driven by glacier calving in Antarctica, was written by Michael P. Meredith, Mark E. Inall, J. Alexander Brearley, Tobias Ehmen, Katy Sheen, David Munday, Alison Cook, Katherine Retallick, Katrien Van Landeghem, Laura Gerrish, Amber Annett, Filipa Carvalho, Rhiannon Jones, Alberto C. Naveira Garabato, Christopher Y. S. Bull, Benjamin J. Wallis, Anna E. Hogg, James Scourse.

Top image: British Antarctic Survey