Charge of the Lycra Brigade

Postgraduate researcher Matthew Whittle explores whether the Tour de Yorkshire will attract more people to cycling?

Competitors in the second Tour de Yorkshire cycling event have begun their three-day route through many of the region’s towns and cities, racing toward the finish line in Scarborough. This event has largely been developed off the back of the success of Le Grand Départ – the opening stages of the Tour de France – which was hosted by Yorkshire in 2014.

Yorkshire’s leg of Le Grand Départ was viewed as a great triumph, generating £128mfor the local economy and attracting an estimated 3.6m visitors to the region. It was said that the event would boost the popularity of cycling – and indeed, the sport is undergoing something of a renaissance in the UK.

But up until now, there has been no detailed research on who attended Le Grand Départ – so there was no telling whether the event did reach out to a new audience. Now, we have used a unique dataset to investigate whether Le Grand Départ was attended by all sections of society – or just “the Mamils” (middle-aged men in lycra).

March of the Mamils

Yorkshire has a relatively diverse population, in terms of ethnicity, 7.3% are Asian, 1.5% are black, and in terms of economic profile, pockets of deprivation sit alongside some of the wealthiest areas in the country. If the event was truly inclusive, we might expect these populations to figure more prominently at Le Grand Départ.

Over 4,000 questionnaires were taken over the course of the three opening days of Le Grand Départ in 2014. We analysed these to pull out the basic demographic information of those who attended. Our analysis revealed that the demographic profile of the spectators as a group is skewed: it is more white, male and middle-aged than the national profile.

Over 97% of those who came to the event were white (compared to 86% of the population who reported as white in the 2011 Census), with the proportion of male spectators slightly over the national average (51% compared with 49%). There was also a clear over-representation of spectators aged 35 to 44 (23% of all spectators compared with 17% of the national population), 45 to 54 (25% compared with 17%) and 55 to 64 (17% compared with 14%). These traits match up with the group popularly known as Mamils.

Even so, we were surprised to find that there was a relatively equal gender split at most locations (bar the “King of the Mountains” sites). According to the National Travel Survey, men cycle more than women: in 2014, men made over three times as many trips by bike as women, with those aged 30 to 49 covering more miles than any other age group. The equal attendance at Le Grand Départ is encouraging, because it shows that events like this may have a role to play in reducing the gender imbalance in the sport.

Access denied

However, the same cannot be said for other demographics: for instance, the spectator group was less disabled (4%) than the national average (12%). And while this is likely due to a smaller proportion of spectators being over 65-years-old, it could also be attributed to the difficulty of access at many stages of the route. Generally, where the route is least accessible the demography of the spectators is more skewed away from the national average.

This is most prominently seen in the least accessible (and arguably most exciting) “King of the Mountains” sections of the race, usually staged in the most rural areas. Here, the proportion of male spectators jumps to 56%, while the proportion of spectators with disabilities drops to 2%. This does suggest that there may be barriers to access for certain groups in the least accessible places.

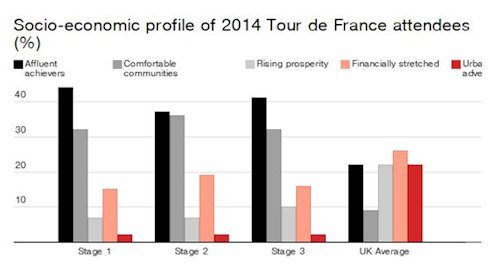

This data was combined with a socio-economic classification to draw a clearer picture of the type of person who came to spectate. Again, we found that the composition of spectators for each of the three opening stage of the 2014 Tour de France in Yorkshire is unlike the national average.

Between 79% (stage two) and 83% (stages one and three) of spectators fall within one of the three most affluent categories, while those classified as the most financially comfortable (“affluent achievers”) represent more than twice the national average at stages one and three. There is variation at different sections of the route: the relatively inaccessible “King of the Mountains” sections were primarily attended by “affluent achievers” (39%) and “comfortable communities” (37%), while the least affluent “urban adversity” group only accounted for 1% of the total crowd at these locations.

The positive benefits of hosting large scale events like Le Grand Départ and the Tour de Yorkshire are compelling. Beyond short-term economic benefits and positive publicity for the region, the social capital delivered by these events should not be underestimated – there’s no doubt that they bring communities together in celebration. But high profile events, which require public expenditure and goodwill to go ahead, should be accessible to all.

Evidence suggests that the crowd who turned out for Le Grand Départ was not particularly representative of the wider population. In the interest of fairness – and indeed longer-term justice in our society – we could, and should, do more to ensure that cycling and other major sporting events are accessible for all.