Resilience planning: the role of walking and cycling in keeping economies moving

Local economic network resilience takes many forms. One major factor is transport resilience.

Transport resilience is the ability of people to keep making journeys to key activities, for example if climate change causes disruption or long term change to the transport system. A recent briefing from Climate UK says Local Enterprise Partnerships (LEPs) need to prove to funders that resilience is embedded in their planning. So, how can this be done?

Ian Philips, with support from Andy Cope and colleagues at Sustrans, has recently completed a PhD which looks at the contribution of walking and cycling to transport resilience. Walking and cycling are sustainable and resilient ways of getting about. For example, they both still work if we have to drastically reduce fuel use to meet CO2 targets. They work even in highly congested conditions, and they work after natural disasters when transport infrastructure is damaged.

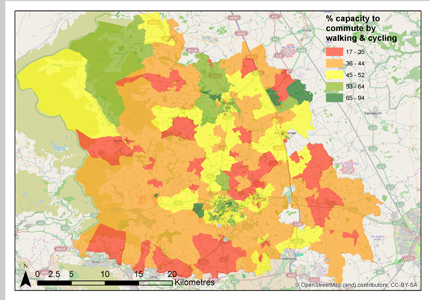

The research starts by looking at who could get to work by walking and cycling if there was no motorised transport available. Though this is a pretty extreme scenario, it is easy to understand, so when a map is produced showing street by street across a whole urban area how resilient the population is, it becomes an interesting way to think about the current level of transport resilience.

Above is an example map from Harrogate District (part of the Leeds City Region and York North Yorkshire and East Riding LEPS). The green areas suggest a high proportion of the population have the capacity to access work by walking and cycling. In red areas with low values, we can test the effect of different policies. In some areas we found simulating the effect of health policies or increasing availability of bicycles led to a significant increase in resilience. The model behind the maps is set up in a way that we can examine what other kind of policies might be useful in different areas; giving a tool that can suggest cost effective targeting of policies to specific areas.

The computer simulation model developed in the research is also set up so that it can be used to ask what-if questions such as:

- If we built a new housing estate, what is the transport resilience of these people likely to be?

- If we built a new business park or hospital what proportion of the staff will be resilient to forced changes to the transport system (i.e. would they be able to get to work by walking and cycling)?

This tool could help LEPs assess and plan for resilience in local transport. The researchers would like to speak to members of the LEP Network who would be interested in a trial application of the tool which could then be discussed more widely across the LEPs. For more information contact: Ian Phillips or Andy Cope.

[In relation to the map: The proportion of each Output Area (~300 residents) likely to be able to commute to work using only walking or cycling in a network with no motor vehicles. Principal data sets ONS 2001 census data, Health Survey for England. Estimated cumulative uncertainty in indicator value at Output Area Resolution ±10.1%. For more details about data, maps, models or methods see Ian’s thesis or contact Ian Phillips. Ian’s PhD was sponsored by the ESPRC and Sustrans, and completed at the Institute for Transport Studies].