Charting a path out of the wilderness for the planet's sake

Most people might think they know what a wilderness area looks like – but they’d probably not quite have the right picture in mind. Yet policymakers need a rigorous definition and accurate mapping of wilderness – or wildlands in countries now devoid of genuine wilderness – to protect this diminishing precious resource.

Which is where Dr Steve Carver, Director of the Wildland Research Institute at the University’s School of Geography comes in. He and his colleagues advise governments and other organisations around the world on the boundaries of genuine wilderness areas and the impact any proposed human activity would have on them.

Mapping and protecting wilderness areas is a vital environmental challenge, Steve says: “Wilderness supports much of the world’s biodiversity and slows climate change but these areas are being lost at an alarming rate. We must recognize their value and protect them. To do that, we need rigorously defined their geographical limits.”

Wilderness supports much of the world’s biodiversity and slows climate change but these areas are being lost at an alarming rate.

Since 2007, Steve and Professor Alexis Comber, who analyses spatial data, have shaped policy in countries ranging from Scotland to Iceland and from France to China. Steve started work in this field by modifying tools developed for his PhD that originally identified potential locations for nuclear waste disposal.

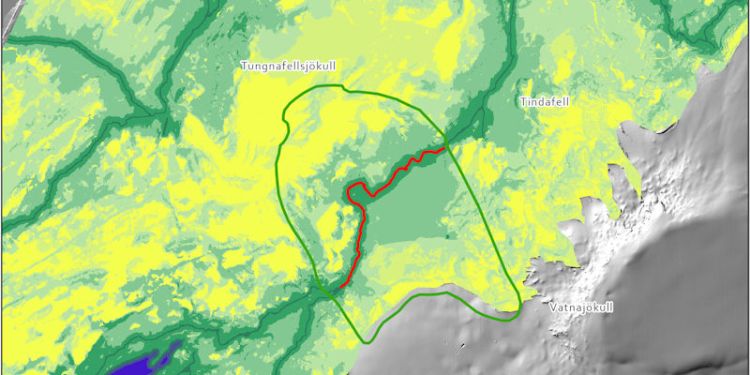

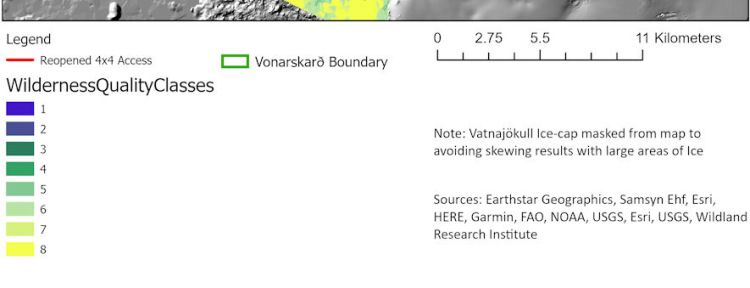

Segment of map of Iceland wilderness: Mapping and protecting wilderness areas is a vital environmental challenge (source: Wildland Research Institute and partners)

Key: Map of Iceland wilderness (source: Wildland Research Institute and partners)

He explains: “For my PhD I used GIS (Geographical Information Systems) technology – which was relatively new at the time – to tabulate a lot of criteria. It’s a tool that supports multi-criteria decision making about a landscape.

“Now I use the same techniques but re-jig the parameters so, for example, you’re looking at factors such as naturalness of vegetation and minimum human population density.”

The tools and software developed by Steve and his colleagues, including in the University’s computer studies department, provide 360-degree visual impact assessments at a more detailed level than before.

“People had done this at a global level but you need to look at things like how long it takes to trek to a site overcoming barriers such as rivers or dense vegetation or forest rather than showing the distance by simple straight lines. Our technology means we can accurately map remoteness and give detailed assessments of how many human features or how much human activity you can see whereas other technologies only give you a basic yes/no answer to that question.”

Our technology means we can accurately map remoteness and give detailed assessments of how many human features or how much human activity you can see.

Steve’s work with the Scottish Government from 2007 saw wildland areas included in Scottish Government policy, a move that triggered the European Union to establish an international register of protected wilderness areas. The team’s approach has also shaped the EU’s 2020 Biodiversity Strategy, which includes a wilderness quality index.

They have also significantly re-shaped wilderness management plans in US national parks, France and China.

Real understanding of a wilderness area, Steve says, comes with travelling through it – which means trips to places such as Death Valley, Iceland and China.

And while we hear much about turbo-charged economic development and the rise of mega-cities in China, Steve points out that the country “has a long history of ecological thinking going back thousands of years – an idea of eco-civilization”.

“To use a Chinese expression that is Ying and Yang with the rapid economic development we hear so much about. They are beginning to recognise that without protecting their ecosystems their economy is completely unsustainable.”

That’s why he has worked with colleges and Tsinghua University in Beijing to map Chinese wilderness and identify areas for new national parks.

Steve is again working with the Scottish Government to harvest the country’s bounteous supply of wind to provide green energy without blighting the country’s wildlands.

It is estimated that globally wilderness declined by 10% in the 16 years from 1993 but Steve refuses to be pessimistic.

“Wilderness is the ultimate resource without which we won’t have any economic growth in the future – everything we have comes from the wild. Rarity value makes things precious so wilderness should increase in value as it becomes clearer how much we have lost.”

Contact us

If you would like to discuss this area of research in more detail, please contact Dr Steve Carver.