Research project

SaferActive

- Start date: 1 April 2020

- End date: 30 June 2021

- Funder: Department for Transport

- Value: £82,107

- Partners and collaborators: Department for Transport; Royal Automotive Club Foundation

- Primary investigator: Professor Robin Lovelace

- External primary investigator: Catherine Mottram

- Co-investigators: Dr Malcolm Morgan, Dr Roger Beecham

- Postgraduate students: 940065422

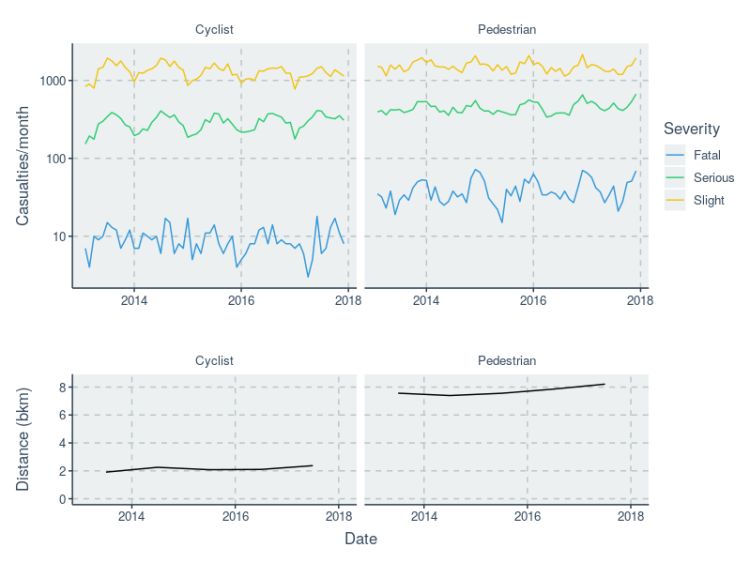

Active transport can tackle some of the most pressing issues of the 21st century, including air pollution, the obesity epidemic, and transport-related social exclusion (Lucas 2004; Johansson et al. 2017; Saunders et al. 2013). Recognising these wide-ranging benefits, the government has ambitious targets for active transport, as outlined in the Cycling and Walking Investment Strategy (CWIS): to double the number of stages cycled compared with the baseline year of 2013, and “reverse the decline in walking” (Department for Transport 2017). Notably, the government aims to double cycling whilst simultaneously reducing the number of people killed or seriously injured per billion km cycled year-on-year. Data on cycling rates and future investment plans suggest that the cycling uptake target will be difficult to achieve (Road Safety GB 2019). Much research funded in support of the CWIS, such as the Propensity to Cycle Tool (Lovelace et al. 2017), has focussed on boosting walking and cycling levels, with relatively little attention paid to safety, despite the fact that cycling and walking casualties have not fallen since the CWIS baseline year of 2013 (see Figure 1). Safety is a major barrier to greater uptake of cycling and walking (Horton 2016; Jacobsen, Racioppi, and Rutter 2009), with fear of collisions and “too much traffic” being the top two reasons cited in DfT research (Nathan 2019).

Figure 1: Active transport casualties have flatlined. Monthly casualty rates by mode and severity (top) and distance travelled by active modes across Great Britain, 2013 to 2018. Credit: ITS Leeds, using the stats19 R package, ONS population estimates, and the National Travel Survey summary statistics (NTS0303).

The research outlined in the previous paragraph suggests that road safety measures can be an effective way of meeting both the active travel uptake and the road safety targets in the CWIS. This raises the question: which road safety measures work best to protect pedestrians and cyclists?

Recent research has found that a range of traffic calming measures can reduce casualty rates, including ‘20 mph limits’ (implemented only via signalling) and ‘20 mph zones’ (which can include optional measures including speed cameras) (Maher 2018; ROSPA 2019), ‘filtered permeability’ interventions including and rising and fixed bollards, and a range of speed humps. A range of additional traffic calming measures is described in the DfT’s Local Transport Note (LTN) 01/07 (Department for Transport 2007).

The focus of this study will be on three types of intervention because these have received attention from the perspective of active travel (Mulvaney et al. 2015), and because data on their spatial (and in some cases date of implementation) is relatively abundant: 20 mph zones, which are well documented in a recent study by Maher (2018), and local case studies published for Bristol (Bornioli et al. 2018) and Greater London (Sarkar, Webster, and Kumari 2018). Data on the spatial extent, attributes and time of implementation of 20 mph zones will be collated from a range of sources, including via .gov.uk websites, newspaper articles and OpenStreetMap, building on research estimating the accuracy of crowd-sourced road data (Barrington-Leigh and Millard-Ball 2017). Physical traffic calming measures, including the location of speed cameras and speed hump data from local authorities OpenStreetMap. Filtered permeability, which will be measured on a sliding scale reporting connectivity for pedestrians and cyclists, relative to motorised modes.

Impact

Reproducible code that accesses, cleans and stores intervention data will be published in an R package, with the working title of trafficcalmr. This will lead to a step-change in knowledge on how to access and process historic road calming intervention data, filling an important gap in current knowledge, and providing a robust evidence base on which future interventions can be prioritised and monitored.

Project website

https://saferactive.github.io/